Van Gogh’s Time in London

I’ve seen only a handful of Van Gogh’s paintings, most of which were residing in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. The museum is housed in an old railroad station on the Left Bank, within a long stroll of the Louvre. It’s a massive block of stone, an edifice built to support the World’s Fair of 1900, hauling visitors into the heart of the city. The museum is also one reason Paris is central to the art world.

Outside the museum, the concrete promenade along the Seine was being decorated by artists in colored chalk as the tourists watched. Performance art in a real sense. And the small vendor shacks with their backs to the river ran for blocks.

Overwhelmed when I first walked into the place, it took time to get my bearings. The train hall interior is a glorious vaulting space with Roman arches and window glass framed in iron with a see-through clock opposite to where the trains once departed. Gare d’Orsay it was called in its train days with four tracks; the trains would back into the trail room to load and unload passengers. The pronunciation gives it that French flavor, even if the translation into English is blunt enough: Orsay Station / Orsay Museum. To a Francophile there’s no arguing the French is sweeter to the ear.

The day we visited, inside lay the glory of Impressionism and early Modern art–paintings, drawings and sculpture, fashion and furniture. We devoted the better part of a day and could have spent the week. I was shooting a 35mm Nikon film camera and taking as many shots as my patient wife would let me. The downside was spending the time to compose, focus, set the F-stops, etc. left me in a photographer’s daze, not able to absorb fully what my naked eyes were registering. OK, I need help.

But from that day’s excursion, I have a framed photograph of an allegory statue, done in polychrome stone of a woman in flowing gown, executed in what might be called the Art Nouveau style, against a gilded, engaged pillar just behind her. [i] Nature Unveiling Herself Her fingers hold the long veil back from her face and torso, almost modestly. She represents the unveiling of Nature as the sculptor named her. Ten years later when I visited her last, she’d been moved to a mix of other statuary in a minor position, as if the style had passed its prime. And by then photography of any kind was forbidden inside the museum. Shooting light available, as any respectable photographer does, made no difference.

Photographing paintings in the Musée d’Orsay seemed irrelevant, so I mostly didn’t. Photographs of paintings, as if the art could be reimagined by reproduction seems a waste of effort. Archival photos have value, but what I’m searching for in these photos by imposing a second medium is another meaning layered on the first. “Oh, look dear. He’s taken a photo of an image…” An elaborate version is Steven Sondheim’s musical, Sunday in the Park with George, based on the painting by Georges Seurat. Signature Theatre, in Arlington, Virginia put on the musical to acclaim a few years back.

Georges Seurat A Sunday on La Grande_Jatte_1884 Google Art Project

Visitors jammed the museum’s painting and drawings salons, so it took patience getting through the scrum. Taking several steps back from Renoir’s beautiful children only meant someone else passed in front of me, so instead I studied his brush strokes so closely, the blur that suggested their rosy-cheek faces was made even more abstract, which is the appeal of Impressionism, that delight in the skill of the brush, the perfect understanding that if he chose, Renoir could outdo his predecessors of the Académie.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir The Two Sisters on the Terrace 1881 Art Institute of Chicago

Though the sculpture in the Musée d’Orsay cried out to be photographed. Each view captured a different aspect. Close ups caught the bronze textures and colors, and further back, the larger context, where the piece is posed in the train station, and other sculpture out of focus just beyond. I sometimes tried for a long depth of field, keeping both foreground and background in focus, but looking later at the developed film, the closely framed shots were often more effective. Standing in a train hall with a swirl of others wandering in and out of view, the noise of the cavernous space, it was hard to keep all the juggling acts of photography in mind simultaneously. What the mind sees in the moment taken to frame a shot can be a world apart from what’s caught by the photo.

I spent several hours photographing Rodin, and other, lesser known sculptors of the 19th Century. There is a maquette of Rodin’s Gates of Hell, along with individual studies, one of which, The Thinker, probably is the best known. Rodin spent years on his gates, and sadly never saw the complete piece ever cast. The Thinker (Le Penseur) is easy enough to appreciate; the Gates of Hell take work. Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise at the Baptistery of St. John in Florence is suggested as an inspiration for Rodin’s gates. Ghiberti is studied in architectural history as an important point in Renaissance art. Rodin, centuries later, takes allegory in a more classical direction, less about church and more about theme. I associate Rodin with the novelist, Victor Hugo. One worked with pen and parchment and the other in clay and bronze, but the link between them lies in how they address the human as opposed to the politics of cardinals and noblemen, the commoner verses the bewigged one percenters of the day.

In the several salons of the Musée d’Orsay that house Renoir and Matisse, Van Gogh resides among the pride of the period, though only a handful of his paintings are hung. There’s no disputing he deserves to be in their company. Yet, moving from pale, soft colors of nature to more violent storms of weather, Van Gogh does not play coyly with his images. Perfumed tea might go with Renoir, but a darker, more bitter brew serves Van Gogh better.

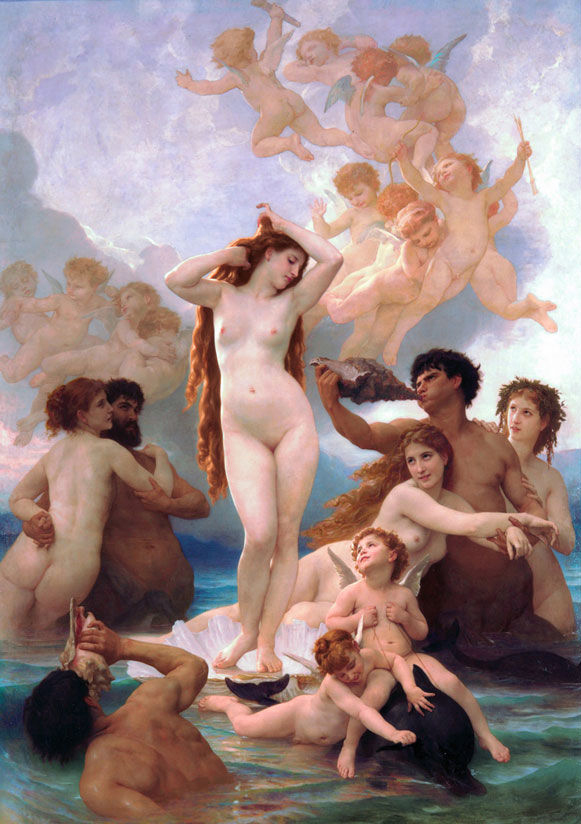

Adophe Bourguereau Birth of Venus .1879

Hard to think that since Botticelli’s painting of the late 1400s no other themes came to the Frenchman.

It’s an oft-told story how the Impressionists grew in reputation from scandalous outsiders to breaking through the stilted French salon art preceding them [i], to pull Western art into new directions. Impressionism and its multiple offspring were the early movements to Modern art. And Van Gogh was a singular genius in that history. Was it because Van Gogh the Dutchman stood outside the Académie des Beaux-Arts that he was free of it? Or had the Académie embraced his genius, would it have evolved? The breaking of Académie traditions is one of the great stories of Western art, the irony of the story being the long evolution from Renaissance to the Académie preceding it.

Everyone knows that Van Gogh was virtually a beggar and out of his mind. You can read how his younger brother Theo supported him financially, and sought to help him through stormy passages of depression and mental breakdown. What’s missed in the popular media is the person. He’s more myth than man. Which makes the story of his time in London a revelation.

VanGogh Starry Night, 1888 RMN Grand Palais Musee d'Orsay Herve-Lewandowski

What inspired this blog was a New York Review of Books piece by Boyd Tonkin, From Writer to Painter: Van Gogh’s London Pilgrimage It’s a great story and a well-written essay. The surprise for me was that before Van Gogh was a painter, he was a man of letters, as the traditional term applies. Dickens was a hero to him. In the letters to his brother, Theo, he refers to important literature, declaring in one “My whole life is aimed at making the things from everyday life that Dickens describes.” Tonkin quotes this letter dated 1882, which puts Van Gogh in London at age 29, before he moves past simple sketches and only 8 years before his death at 37. In the stories I’ve read about Van Gogh, his letters to his brother are mentioned, but not their content, which is as great a misreading of an artist as it comes.

“Posterity has adored the image-maker but ignored the writer and thinker behind them.” Would Van Gogh have cared? In the sense that he wanted to be recognized as making art, yes. Tonkin’s essay isn’t speculative but well researched. A link to the available letters of Van Gogh is provided: vangoghletters.org Presumably a full biography will follow; here’s to hope.

How does a man take up painting with such ferocity so late in life? Tonkin comments on the paucity of his interest in drawing as a boy; one expects to see signs in youth pointing to a life’s passion as great as his. Instead, Van Gogh used language to shape images of the world he saw around him, much as any good observational writer does. But how did Van Gogh draw from literature the inspiration to pursue visual art? It’s a staggering shift. In Van Gogh’s case it appears his love of literature gave him the impetus for his life’s great work, almost as if he’d backed into it. The words of writers Van Gogh admired gave him a source far from where he took it. His letters are nothing like the image of Van Gogh derived from the art world.

Would Van Gogh have lived a happier life without his falling into art? The gift of himself that he gave the world didn’t ease his torment, but perhaps it forestalled his suicide. There are enough stories of people anesthetizing themselves sufficiently to tamp down stray sparks of spirit. If he was better at living a middle class life, perhaps it would have suited him well enough, even if he’d have been lost to the larger world. Did his art lead him too close to the edge, or did it maintain his life longer than he might have lived without it? In The Creating Brain,[ii] Dr. Andreasen says genius is a different animal from the rest of us, that it’s not merely difference by degree. She also says that genius frequently lives in proximity to insanity. I didn’t first pick up her book expecting to read of that, but I’ve been haunted by it since.

Between his mother’s flowering of creativity, from sculpture to drawing, painting and writing, and his father’s dogged pursuit of design and writing, Ryan never stood a chance.

Ryan’s Cobain sketch

Thinking about Paris. Thinking about French architecture in the gothic period. Thinking about Notre Dame de Paris. The spire that collapsed was not built in medieval times, which was probably news to Americans who just assumed it was constructed in a year or two. But the spire was added later in the 19th Century. President Macron has bravely declared that a design competition should be held for its replacement. I say bravely because the thought of doing anything other than recreating the lost spire wouldn’t occur to most. Mon Dieux, le scandale! The difference between French political leaders and this country’s stands in stark relief; the French know their culture.

[1] Ernest Barrias’ Nature Unveiling Herself, 1889 The museum’s description gives the following: “The statue was commissioned in 1889 to decorate the new medical school in Bordeaux. A young woman, the allegory of nature, is slowly lifting the veils she is wrapped in. When he had finished the first version in white marble for the school, Barrias designed a second statue in polychrome, for the ceremonial staircase of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, in Paris. He used marble and onyx from the newly reopened quarries in Algeria.

“Carefully carved to enhance the decorative qualities of the materials, the various parts of the statue play on the veins in the ribboned onyx for the veil, the mottled effect of the red marble for the robe, the preciousness of lapis lazuli for the eyes and malachite for the scarab and coral for the mouth and lips.

“The overall effect is surprisingly rich. The work belongs to a major revival of polychrome sculpture launched by archaeological discoveries and illustrated fifty years earlier by Cordier. The statue was very popular and many copies were made.”

An extended discussion of Barrias’ work can be found at: Caterina Pierre on Barrias

[ii] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-impressionists-artists-dominated-parisian-art

[iii]The Creating Brain: The Neuroscience of Genius by Nancy C. Andreasen. ©2005.An extended excerpt can be found here: http://www.dana.org/Cerebrum