The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down

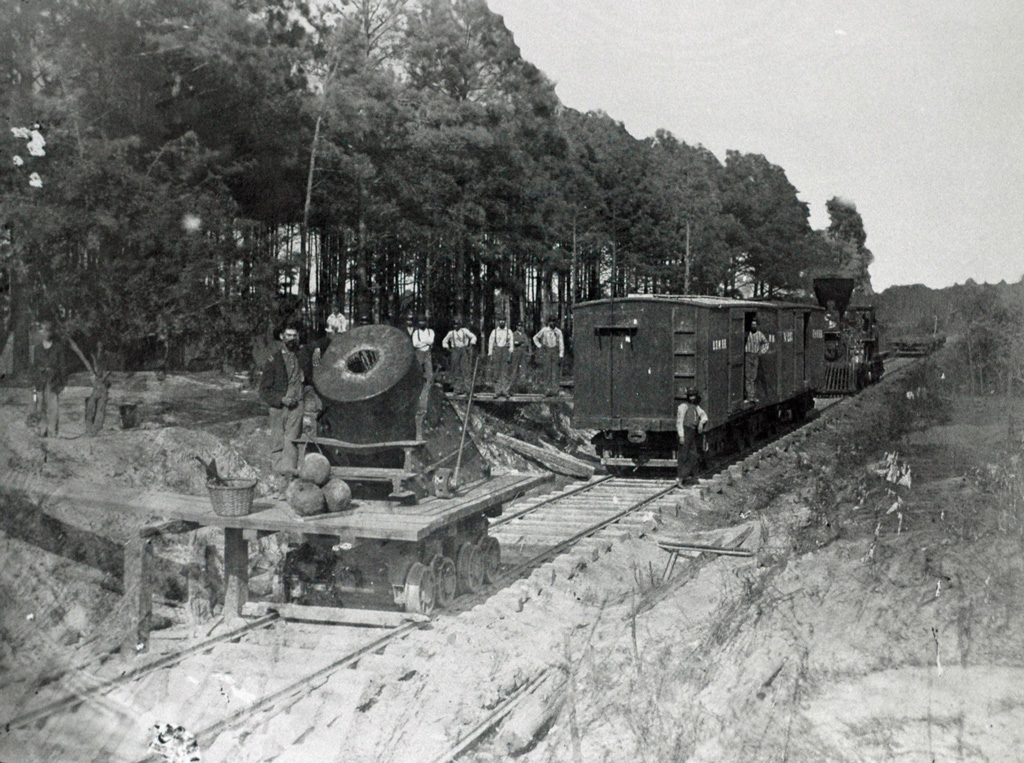

On the rail line from Danville, VA. Hal Jespersen. Taken from collection at US Army Military History Institute.

How long has this song been playing in my head?

Standing in the art studio, wielding one heavy lithography stone against a second, grinding one against the other for what seemed an eternity or more to erase vestiges of a previous image, then laying strokes of litho crayon on point then sideways, unskilled except for a desire to create, painting the finished stone with gum arabic mixed with nitric acid, prepping and pulling the wet paper away from the press to reveal the sketch of a smoking wasteland resembling a destructed country such as the plains of Gorgoroth (place not the band). As strange a scene as that, as unusual a music as the Band playing full volume in the drafty studio, I was stepping into a life where nothing seemed familiar.

That is how long I’ve tried to balance the heartbreak of broken white southerners with the larger corruption of American slavery. Mercy for the departed.

Levon Helm’s vocals were an old leathery redneck’s a long time before he grew into one. That twang was as distinct as a coon dog’s howl, and it’s stayed with me for a lifetime, though the lyrics were Robbie Robertson’s. Is evil an ordinary blindness, or as pressing as the need to feed and shelter a family? The conflict between a moral high ground and living day to day haunts the song as it haunts this country’s history.

The lyrics seem to turn on a sighting of the great man riding by. With a single phrase, the contrast between commoner and lord is made clear. But Robert E. Lee was somebody’s baby. He didn’t choose to be born into a world of white lords and black slaves. He didn’t have a choice but to be loyal to his own, did he? The Union was so new and too uncertain; Virginia he was told from the crib was his home, the rolling hills and deep shade forests.

Lee swore an oath to this new country, but at a personal crossroads, he chose the wrong path forward. He is admired still for being steadfast and loyal, sadly to the wrong cause. Even leaving aside the evil of enchaining other humans, men, women and children, the horror of it, there still lies the question of loyalty to a greater future contrasted to a calcifying past. Bless his bones.

After he swung down off Traveler, what did the rest of life hold for Lee? He surely rode past those poor, limb-lost veterans, saw their poverty and the ruination that ran through his country after its defeat. And the slaves who’d been freed, where could they go and who would offer help? Did he ever beg forgiveness for his role in cursing his beloved Virginia? Or beg forgiveness on his knees for ordering his countrymen to march across an open field to die in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg?

If Virginia had voted to remain in the Union and turned away from the rabid hate born in Carolina and Georgia, if Virginia had faced the moral implications of slavery, how would Virginia’s leaders such as Lee appear to us now? Lee got no vote in succession since he wasn’t in the Virginia legislature, though surely a person of his stature should have swayed those grim fools. So can he be forgiven? Mercy.

Folk who had sent their best and bravest, their boys to fight under Lee’s command, the ones who struggled their entire lives keeping roofs over their families, what did they have left after Appomattox? No white horse for sure. But surely they, this many years after, can be forgiven for clinging to a failure they had no chance to correct, Virgil Caine among them.

In kindness to the dead, they should be respected, but what can be said for those who still today see value in a lost cause? Like the country boy living in Ohio in the present day mounting rebel battle flags both sides of his pickup? Ohioans died in that same war, fighting for their brethren and the Union. The kindest thing you can say is that he’s not read much history.

The American Civil War broke the South on an anvil of gruesome fighting, but it didn’t free the slaves. Not in the way Lincoln nor the abolitionists prayed it would.

The United States is an idea, at the foremost a work in progress. We are far from done. First written by slave holders and ambitious shipping magnates from Philadelphia north to New England, yet it was that time’s miracle. Jefferson wrote the Declaration yet fathered children by his own young slave. Washington’s slave plantation is a tourist destination these days. A staggering number of slaves came through New York City. No better than the Irish immigrant coal workers who came after, though at least the Irish were free to starve on their own.

It’s a cliché to say humanity is tribal. But with an entire planet filling fast with people, we need a further evolution in this country. If Americans still believe in a higher calling, we should return to serve as an example to the world, not because we’re superior but this is where the country began. To live in a country of foreigners, to live by those others who have come here as our own ancestors had, the same strange ways we all came, to atone for the sins of our fathers and beg the Indians their forgiveness and welcome our black brothers, is this not what we Americans should be about?

My son was born in Florida but on his mother’s side comes from South Carolina. There is a low country plantation in his Carolina lineage, and family bibles from that sad era that I’ve held in my hands. Inside of which I saw bills of sale for several of the slaves bought in the Charleston slave market before the outbreak of war. $1,800 for a human being, $700 for a child. I expect when my son inherits these, assuming I’m still able, I hope we’ll drive to Charleston, find those persons’ descendants, and return those sad papers. They belong to other families, not ours.

In a Union artillery battery, my great grandfather fired grape shot at Antietam, so the story goes. I’ve walked Bloody Lane there; I’ve seen photos of the piled dead soldiers. Years later, James Brown abandoned his family to wander off, until he came back home to die. PTSD wasn’t heard of, though maybe his wife did know when she looked into his eyes.

Small graces won’t buy forgiveness, but may help ease us into heaven.

To pick up a twenty pound stone, carry it to the washing tray and proceed on faith to create something originally born from Tolkien’s greater imagination, an evil he named Morgoth, listening to songs about French Arcadians exiled to Louisiana, written by one whose mother was Indian and liked wearing a broad brim hat playing in a band of other eclectics, all of these things are surely a start.

“Nothing I have read … has brought home the overwhelming human sense of history that this song does. The only thing I can relate it to at all is The Red Badge of Courage. It's a remarkable song, the rhythmic structure, the voice of Levon and the bass line with the drum accents and then the heavy close harmony of Levon, Richard and Rick in the theme, make it seem impossible that this isn't some traditional material handed down from father to son straight from that winter of 1865 to today. It has that ring of truth and the whole aura of authenticity.” Ralph J. Gleason Rolling Stone, October 1969

i “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” Robbie Robertson, recorded by The Band in 1969