Is Architecture a Trainable Skill?

Yes, but you have to want it–and be a glutton for punishment.

Returning on the Beltway from Tysons with a month’s supply of caffeine capsules for the Nespresso machine to support my morning addiction, a thought ran through my head about why architectural design still holds me in thrall (thematically speaking). I was writing years before I designed a real first building, yet architecture will stay with me no matter if I never design another. Some are skilled at many things; I believe they are called Renaissance people. Me, I’m mostly good for designing buildings and writing.

I write from need and design out of curiosity. Or possibly the other way around.

In a middle school geometry project, I redrew the blueprints my mother kept of our house in Sumter, S.C. I explained that my drawing was a demonstration of geometric shapes, when really I just liked drawing the plans. That same year I checked ‘architecture’ as what I planned to study in college, though I had no clue what that entailed, blissful dreamer that I was.

In his lifetime, John Hejduk made a credible argument for drawing fantasy buildings as an end in themselves, teaching architectural theory as main profession. He got a lot of airtime in the architectural press. Piranesi [1] did fabulous etchings of stage sets among other flights of the stuff. Piranesi was more my man.

The Tower by Giovanni Piranesi

Created: 1761 date QS:P571,+1761-00-00T00:00:00Z/9

Design at its essence is a dive into a world yet to be constructed–arguably a fantasy. Before the invention of CAD software, it required imagining a 3D space in order to create 2D drawings describing it. Even 3D fixed renderings depict only a static 2D view. The inverse was/is being able to ‘read’ drawings. Today we have real-time walk-throughs, fly-overs, birds’ eyes and more, come on down!

Regardless, the question remains, where does that underlying image spring from, and how might it evolve into an actual inhabitable place?

The training of an architectural mind is born from a native imagination for object space, molded by the fulltime work of design. As an undergraduate, walking to an early breakfast straight from the design studio was a not uncommon event.

The Sunday one of my fellow crazies strode across the drafting tables in his tidy whiteys (having just woken up) about the same time our resident blowhard, Tommy arrived to tour the studio with his parents, all three dressed for church—well, it brought the fatigued studio denizen down in gales of laughter.

After graduating school, most architects (in this country anyway) will never again spend as much or as intensive a time focused solely on design. 3:00 AM revelations don’t come quite as frequently going about the business of architecture, as opposed to its design. Yet without an initial design/image/vision et al., the rest is a waste, hard work though it may be.

First you need to love drawings, then you study what the drawings imply. A strong partí emerges from compositions of plan, elevation and section. Not that any but design geeks might ever study those 2D abstracts. When you view a strong piece of architecture, the composition lies at the heart of it, even if it’s not always discerned. And when an awkward composition (misproportioned, perhaps looming or just ill-mannered) is built, no theory of current fashion can confuse the fact.

These 2D sketch composition drawings are shorthand studies. Since the arrival of CAD software, young designers often mistake them for being unnecessarily quaint. But if my compositions work in plan, section and elevation that the design will work. I also admit to knowing where they break down. If I were to write a syllabus for an architectural education, even this late I would seek to blend the pencil with mouse and keyboard.

Design is this curiosity about how an imagined view from a full length window, say, might seem. Textures and even sounds that can seduce the viewer.

If you are walking across a bridge, say approaching an entrance, what else might you be pleased to see? Is the all-important door or the view beyond more important? Sleight of hand is also a technique.

Door at the end of a bridge

Photo by Eric Taylor Photography, 2014

A building’s response to its context is an essential part of what its design should be about. You can choose to blend with the site’s context–what’s already there–and quietly burrow in. Or stand in contrast (as a library might be distinguished from the commercial strip.) Or simply look for clues in the surrounding scale, materials, solar orientation, to create space for people. You can’t create a building independent of its environment and expect it to be meaningful. Not an original thought, just what I’ve learned.

Shirlington Library & Signature Theatre fronts the small plaza with activity, particularly at night when the glass theater lobby above comes alive.

I can’t explain how I found my way through architecture school but do recall developing year over year. And what sticks with me is that I needed to learn for the most part on my own. That’s not a conceit; I just needed to work it out for myself. It was an internalization of a thousand examples, the absorption of concepts and the discovery of a few others at three in the morning.

The professors at Clemson were training us in the basics of logical floor plans and rational building design in the Modernist mode. As I saw it, the modernists were boring. On campus, the Clemson library is a good example of ‘classical modernism’. The Kennedy Center in Washington, DC is another; the lobby with red carpet and tacky chandeliers looks like the world’s largest movie theater. Its best feature is the exterior promenade overlooking the Potomac–provided you can dismiss the noise and fumes of the traffic roaring beneath. The Futurists believed that speeding trains would be the future. Speed Kills.

During the time at Clemson I grew interested in Corbu’s Rochamp chapel, Saarinen’s Yale Hockey Rink, his TWA Flight Center at JFK, and Dulles Airport. Saarinen’s free form geometry was an early design influence, an early aha moment. When I discovered the Ecole de Beaux Arts student bound theses in the Yale Art and Architecture Library, my eyes were opened to just how much more work they did in decorating their designs.

Chipboard Portfolio

In applying for graduate school, the Yale instructions stated that a portfolio, while encouraged wasn’t required. The school did require GRE scores. The University of Pennsylvania specified they didn’t want test scores nor portfolio; they were recruiting the under-represented minorities, as Dr. Cooledge warned me. His skepticism about downplaying skill over background was consistent with his demand that students didn’t go slack in their education.

Harvey Gantt (later mayor of Charlotte) was the first African American to graduate from the School of Architecture at Ben Tillman’s Clemson. One class ahead of mine, Ray Huff has gone on to a great career centered in Charleston, S.C. In neither case could you say they’d been cut any slack to get where they did–though I also don’t know if U of P’s open door policy worked out. My class at Clemson had only three women, none of whom graduated in architecture. Progress was barely beginning on both fronts in the 70s.

Dr. Cooledge’s end-of-year exam was an essay question–‘describe the historic context from the earlier Greek and Roman civilizations leading to the collapse into the medieval as it related to architecture through those periods.’ I heard groans in the lecture hall when he handed out the test. Basically he was looking for a review of the course. Essays I could do, and I hadn’t missed many days of his lectures. Took a couple hours to write, but the A+ was one of the proudest I received at Clemson.

Clemson faculty said they wanted a year of my life as an intern before applying to graduate school, something I didn’t want to wait to do. So, dreaming big, I set about creating a portfolio for Yale. Other than making good grades in design studio by my senior year, I had no sense of where I might fit, so I needed a strong effort at applying. Making matters harder, Yale accepts undergraduate degrees from other disciplines, so I didn’t even have that advantage.

By this time, I’d learned to draw ink on board (where you couldn’t make a mistake without it showing). Clemson drove presentations hard, and I’d survived the ordeal. But for the portfolio? I’d never done one and had nothing to go on. I planned to use photographs of school drawings and models, not very large prints so they didn’t ruin my checking account, but how to mount them?

There was a presentation style I’d seen using chipboard, the cheap, gray stuff we used to model landscapes, glued in stacks to resemble natural contours. Also used for study models, as chipboard was much cheaper than poster board. But what I liked most was that cutting it with an x-acto blade didn’t expose a different colored core. To keep a constant finished face with poster board, you needed to miter the corners; chipboard kept the same dull gray color throughout, so butt-joined corners weren’t ugly if you cut them cleanly.

One of my Clemson presentations was drawn on brown butcher paper–I’d seen other students use it and thought that was a cool trick.

For the portfolio, I mounted the photographs with double-sided tape to the chipboard ‘pages’ and carefully labeled them in my best hand-lettering (another hard-learned lesson) and using a hole punch to fasten the pages with clunky key rings on account of the book being so thick. Then formed a slip cover over the whole thing. The effect I was trying for was cool funk. What it accomplished was more like a poor man’s publication.

When I asked Dr. Cooledge if he’d write a letter of reference, he put this to me: “I can either write a letter to I.M., since we were at Harvard together, or I can write to Yale, one or the other; which would you like?” (I. M. Pei ran a little architectural practice in New York City.).

“I want to go to Yale.”

“Good choice!”

I never saw the letter Dr. Cooledge sent Yale, but I’m sure it was what got me accepted, the portfolio probably just convinced the admissions committee I was church mouse poor–which was true enough.

My other explanation to friends was that Yale needed a geographical representative from a small town in South Carolina, its version of striving for inclusion in the 70s.

We had students from around the world. Wong was from Taiwan, another from Greece, another from Portugal, even Moose, who could draw like a madman, was from Arkansas. And yes, there were women in the class–good designers destined for successful careers. One woman was working on her law degree simultaneously pursuing her master’s in architecture, which was really overachieving, in my opinion.

We were treated as peers; Yale was kind to young, burgeoning egos but didn’t warn us of what lay ahead in the profession. It was all glorious design.

I learned to design by section at Yale. To explain, if floor plans are horizontal cuts (sections) through a building, taken at a few feet above the floor looking down, building sections are vertical slices showing changes at key points, such as double-height spaces and sloping auditorium floors. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) creates a series of sectional images, say of your brain. A building section is much the same idea. Keeping in mind that 2D drawings were a principal tool of design in those days.

The project was for Amherst College in Massachusetts. The school had finished a newly built academic building on a freezing, wind-swept piece of land, to which we were to add a second building. From our sole, mid-February field trip, what I brought back was the memory of freezing my tuchus off. That, and unlike Yale at Amherst there was “no there there” as Gertrude Stein said about Oakland [2]. My design partí for the project comprised oval lozenges like streamline rail cars linked in a series defining a second edge of a proposed quadrangle, a collegiate icon dating from the time of Thomas Jefferson’s mall at UVA. Like a space age wagon train, linked by glass tubes riding free of the land. The series of building sections I drew became the explanation of the idea.

Today, if I am a decent architect, it’s due to those who taught me, beginning with Dr. Cooledge. A three-hour talk to students at Clemson by Louis Kahn convinced me the need to pursue a master’s degree. His words about the brick wanting to be an arch made me smile. Then came Yale: Charles Moore, James Stirling, Henry Cobb, Richard Meier as a lecturer, Lew Davis, Samuel Brody. In 3rd Year I’d wrangled a seat in Alvar Aalto’s studio, only to join the general mourning of his illness and death before he could travel to the States. I’d come so close to an early modern genius.

By comparison, I’ve learned writing from reading. While I was busy getting an architectural education, others were getting their MFAs. It might have helped me write with more depth and polish, and certainly I’d have read Proust a lot earlier than I did. My theory is that writing is harder to teach than architecture because it lies intrinsically in each individual. Though, like architecture, you need to be a glutton for punishment.

Bill Mitchell

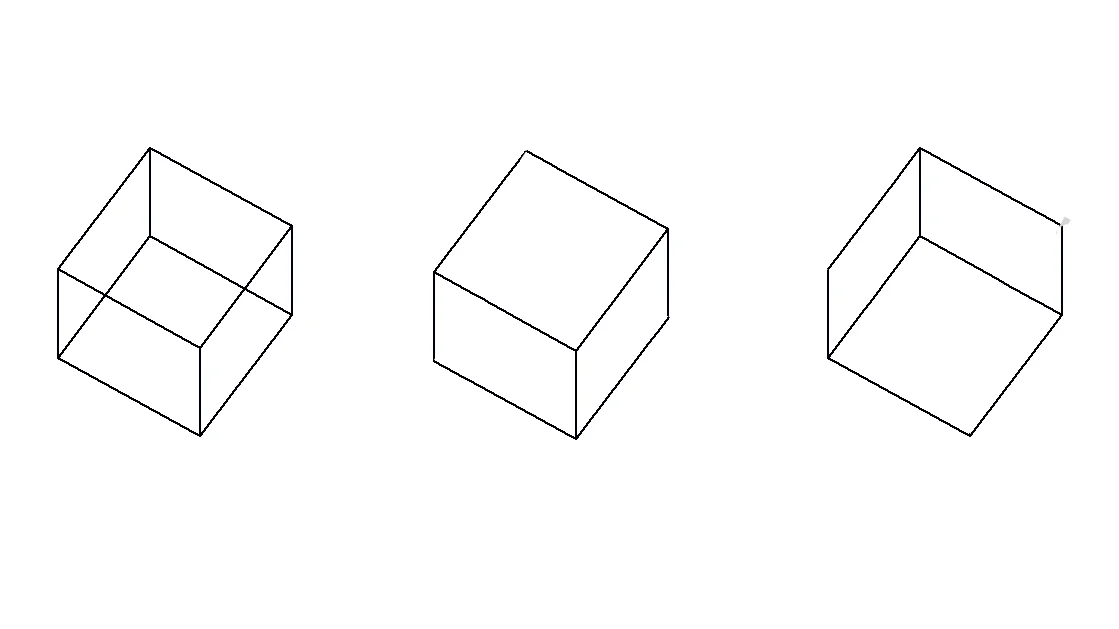

For his thesis, Bill Mitchell wrote a computer program to remove the hidden lines in a wireframe model. Think of a wireframe cube, simple enough for a computer to draw. Now remove all the edges you can’t see in a particular view, i.e. hidden lines. Then change the view and do it again. Do it for any view you ask of it. Write the program in Fortran II using punch cards, please. State of the art computing on main frames the size of Texas.

Wireframe box, 3D box viewed from above & 3D box viewed from below

One day in passing at the Yale Computer Center (with its tapes whirring on the massive banks of computers) Bill said, handing in his punch cards “all this will be software someday.” Not that long after his profacy, it became true.

Me, I was painfully keying in a Fortran program to draw the 17 2D symmetry forms from crystal theory. Hardly much use unless you wanted to draw snowflakes, but it was fun.

I saw two paths for myself–one following Mitchell into a search for the tech tools the profession needed, and the other, staying with designing buildings. Computer programming was intriguing. Still is. Though my heart has always been with design, even though technology often made me wonder, what if?

Mitchell was a visionary; I just wanted to design building using his cool tools.

photo of William J. Mitchell 2010 NY Times obituary

Opinions Like Carbuncles [3]

They teach architects to have an opinion about Design. In the real world, it comes with the necessity of having to decide which of the many options available will be the best. Though this has the awkward consequence of carrying over to other situations. First you get trained to hold an opinion, then you must learn how not to come across like that. Odd way to live.

“Why do you always look up at the ceiling?” My ex used to ask.

“Looking for mistakes,” I’d mumble.

A number of years ago watching a documentary on the Getty Center being built above LA, there’s a scene in the documentary where the Great White himself, Richard Meier doesn’t get to have his way, even has a meltdown on camera about his vision for a landscape element—to no avail. The museum director won that one.

In school I had been prepared to dislike Richard Meier for all the pretty white cubist houses he’d designed in his early ‘white years.’ White was his mantra–was blue already taken?

When Meier arrived to participate in the jury for Henry Cobb’s urban design studio for a project sited in downtown Boston, Meier was impressive in his knowledge of urban space. He’s gone on to prove this with such buildings as the High Museum in Atlanta and the Getty Center.

That same jury Charles Gwathmey had a chip on his shoulder the entire time, and Peter Eisenman whose House VI was his second built work–do the math–as his wont was babbling into the ozone. “An inaccessible void” he declared lay in another project, and I will rest my case.

I have to believe the soft spoken Henry Cobb, descendant from a line of Boston’s Cobbs, hadn’t put the jury together; probably one of the associate professors had.

Gwathmey had a reputation for browbeating students and wearing body shirts to Yale juries. My best Gwathmey story is about another presentation of a classmate who teased him to step out from the strictures of ‘modernism’ to ‘post-modern.’

“You should try this post-modernism, Charlie. It’s fun!”

The comment broke up the entire gathering. The great man was not amused. But Andres Duany continues to be a designer of genuine communities with a keen sense of irony. By a hardy vote, that day’s audience figured he’d won.

Henry in Hell

I liked Henry, a partner of I.M. Pei. Pei Cobb Freed and Partners was the name of the firm. I didn’t get a huge amount of face time with Henry Cobb, mostly because the firm was being threatened with extinction. This was before I.M. was raised to sainthood with his design for the Louvre.

John Hancock Tower, Blue Hour 2013, photo by Tim Sackton

Henry Cobb designed and oversaw the John Hancock building, a sleek, 62-story parallelogram high rise, towering hard by H.H Richardson’s Trinity Church, a Boston landmark from an earlier time. Seems the glass in Henry’s tower was ‘failing’ (engineering euphemism for shattering) descending on places below, including one restaurant. You can read about it.

Hancock (not the capitalist/patriot but the firm named in his honor) settled with the restaurant by buying it. But the rumors of the tower causing Trinity Church to sink in the mud wouldn’t go away. Since that entire part of Boston (known as Back Bay) was once a tidal swamp, it wasn’t hard to believe.

You could see the stress in Henry’s eyes, though he didn’t talk about it and I wasn’t rude enough to ask.

At some point Mr. Hancock’s firm sued Pei Cobb Freed, along with anyone else associated with the cursed project. I have several photos somewhere of the temporary plywood covering pieces of the tower like scattered camouflage.

In his later book Henry N. Cobb Words & Works, Henry writes about the design, “It [John Hancock Tower] is also as close as I have ever come to silence. The building’s restraint to the point of muteness, its refusal to reveal anything other than its obsession with its urban context, is surely its greatest strength but also its ultimate limitation as a work of architecture. Despite the forcefulness of its gesture, the tower remains virtually speechless, and this resolute self-denial is, in the end, both its triumph and its tragedy.”

The man who stood by my desk, politely critiquing what I’d done, was evidently as critical of himself as he was gentle to his students. At the time I was investigating laying three hexagonal grids at odd angles to each other to test the resultant geometries on an urban block in Boston. I was trying for angular pedestrian corridors and plazas leading into the project’s interior like one might discover in Italy – or in a Charles Moore project. Henry never laughed; he must have known I was having fun.

At Clemson’s backwater location, we were disconnected from the mainstream architectural community; at Yale we were swimming in it. I thank the Clemson professors for teaching me fundamental skills, but more I praise Dr. Cooledge who brought me to Yale to hear directly from masters. By the time I came to work for Harry Weese, I’d learned to listen, but also to draw my own conclusions, giving me this passion for design.

[1] Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1720–1778.

[2] Three ‘theres’ in one sentence; a new land record!

[3] Strictly in the gemological sense…