November Blues

Last day of our fall vacation on the Outer Banks, I was outside on the deck waiting for the sun to go down, studying the empty houses closed for the season and thinking about design. With all the sunset photos I’ve taken over the years, the close-of-day fits the season. We’d met with a builder earlier that week who told us the cost of construction hadn’t dropped since we’d talked to him in the previous spring. Building materials were still out of sight, and finding good carpenters was a struggle. “My recommendation is to wait for next year.”

The oversized 5-bedroom house I’d spent months designing indeed fit the site and would have fit that Southern Shores neighborhood. The thing was, it wouldn’t comfortably fit our budget, and I’m reaching the time of life with an end date. D swears she’s retiring soon enough. So why the hell would we want to build a five-bedroom vacation house? Perhaps a smaller one when I was gone to the big charrette in the sky and she decided to retire to the Outer Banks.

And of all the places.

It’s hard to discount the impact of climate change. It’s sad what happened to Sanibel and Captiva just a month ago. The hardy folks living year ‘round on the Outer Banks know about hurricanes, and they’d like to think they wouldn’t be caught by surprise, but low ground is low ground no matter where.

Our site is secure from flooding—for the time being—being 40-some feet about sea level and well back from the shore, but if we were going to rent it in season, it would need to compete in the rental market—five bedrooms, swimming pool, or so I thought. But why the hell would we want a five-bedroom affair in the off season—the time of the year we love best?

The logic seems lame, given a chance to think about it.

Just after hurricane season (some years) and the out-of-towners aren’t flooding the beach. Fall on the Outer Banks is still mild. Hiking a blustery December beach in a misty rain satisfies the soul—when you look down the way and see a solitary beach walker with dog. Even the seagulls are hunkering down. And the oysters are just a few bucks a pound at the Carawan Seafood Store.

Sunset on the Outer Banks—photo by William E. Evans, © 2022

So I was sitting on the deck, finishing Richard Ellman’s biographical sketch of WB Yeats, when this thought drifted in on the breeze—to thoroughly confuse the metaphor—from the sea and the sun going down: Instead of loping off two bedrooms from the plans I’d already done, what if I started over? I was already bored with what I’d done—it happens—and I was reminded how long it had taken to settle on a design for our house in Lake Barcroft—and the one before that which had never been built…

…

If you travel far enough south—to the Caribbean for example—indoors and outdoors flow together. In contrast, Maine summers are too short to enjoy that kind of life. The Outer Banks, if warmer than Maine, more match it for all the gray winter weather, and when one of those named storms comes churning up the Atlantic, one wants a real shelter.

The nineteenth century life saving stations gave the Outer Banks a signature imprint, designed by architects well versed in the period’s Shingle Style. The Gray Ladies of Nags Head passed along another take, combining the shingle style with the low country plantation houses. Seeing one of these, there is an indelible image of shelter from several centuries of storms—famous storms.

…

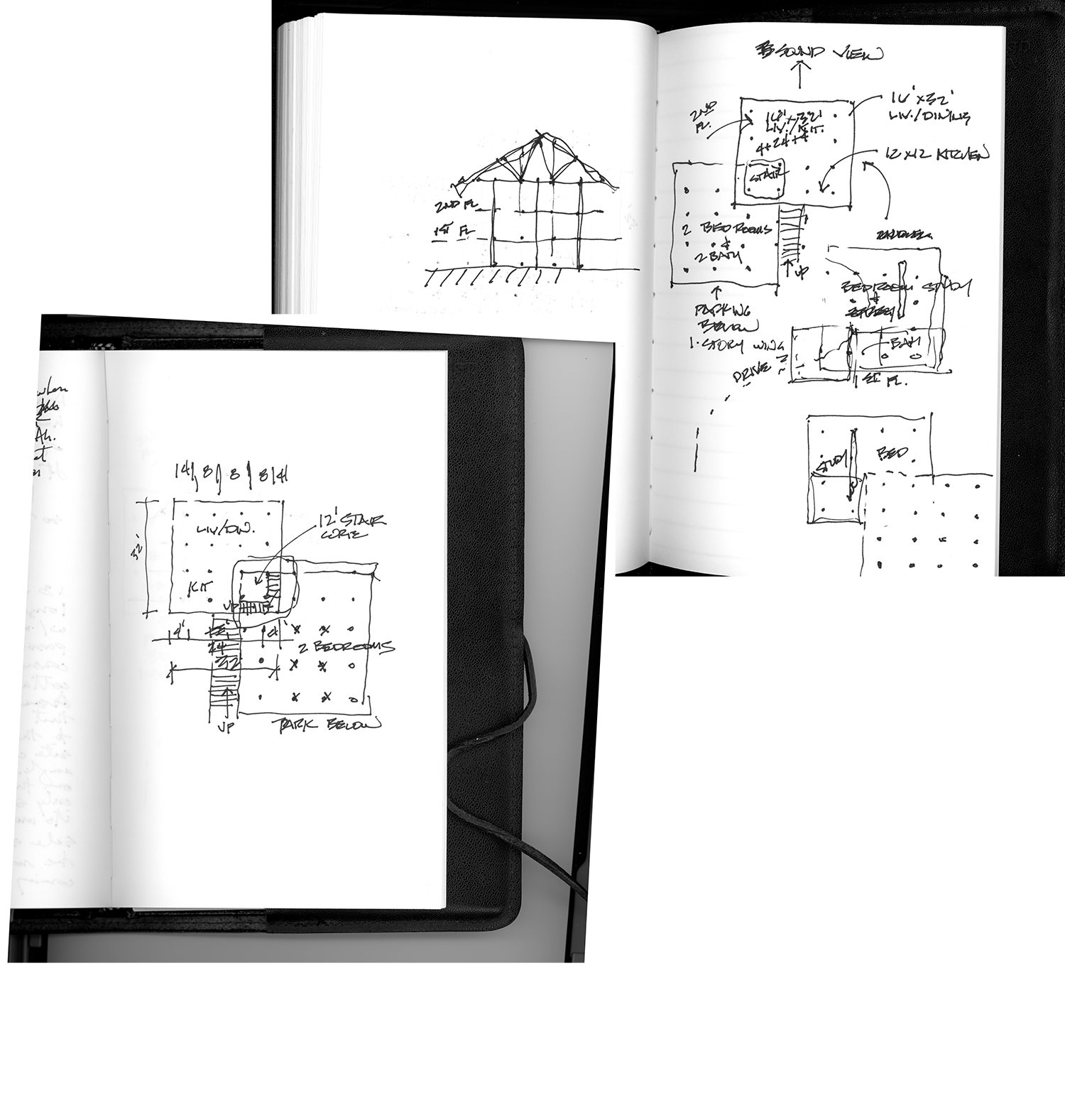

It’s hard to delve too deep in design without a chapbook and pen—same as it is to write—dreaming won’t cut it. You need to set it down. As Steven Pressfield says “Do the work!” So I set Ellman down and took up my chapbook—with its blue leather image of Hokusai’s woodcut, The Great Wave off Kanagawa. He did the woodcut around the same time as the Gray Ladies were being built half a world away facing another ocean.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa – ca 1830 by Katsushika Hokusai - Metropolitan Museum of Art, online database: entry 45434—Public Domain

Hokusai’s famous woodcut carries sad meaning for my family—and the blue leather version, a birthday gift from D, has carried a good number of poetry drafts about Ryan. It became a ritual practice, this sitting in a late sun by an ocean trying to hang on.

…

The building site largely faces west toward the watery expanse of Currituck Sound, but there’s a magnetic pull to the view toward the southwest. Way in the distant you can see the Route 158 bridge crossing over to the mainland. Plus the houses in the immediate foreground are further removed. The view if not the site itself is canted in that direction. Working the previous plans, it was apparent, but I had no way to orient such a long bar of a house in that direction.

Early on, I had a notion of a shingled house on the rocky coast of Maine designed by an early Modernist like Edward Larrabee Barnes—or an earlier Alvar Aalto’s ‘village’ assemblage. An image of two wings barely joined by a connective glass transparency on a platform deck. Not exactly Outer Banks, but the idea was to set the platform low enough for cattails to surround it with the two wings sheltering the platform’s center.

I had tried the form several times, but five bedrooms projected too far forward given the property’s slope. The elevation I needed for the view would fall away too quickly for a house set on pilings. So the design became a straight bar across the top of the site. It fit the site but it didn’t fit our budget. A smaller footprint might work better in both regards.

So I filled several pages in the blue leather chap book. Take two squares, each thirty-two feet on a side, shift one square forward and insert the circulation core at the crux. Took less than an hour to sketch. On the far side of the deck, Layla was catching a last of the day nap while the sun was going down. That evening the three of us headed to a sound-side restaurant for quiet dinner on an outside deck and a sustained sunset for our last day.

Sketches by William E. Evans, © 2022

This worked down to two twenty-four foot squares—and a third, middle square tying them together. Recalling the natural pull toward views of the southwest, the site’s inclination suggested an asymmetry. Or a diagonal symmetry.

Returned to Northern Virginia, the following weekend produced the first plans. The image being so clearly engraved in my mind, all I needed were trace sketches to test it. Several more weekends were required to confirm it was worth attempting.

It was a thousand square feet less than the previous design, and I’d found a central form I’d been thinking about for years. It takes fuller advantage of exposed wood framing, involving the stair at the heart of the plan. instead being an object projected from the bar, the stairs can be at the core, an armature so to speak.

Done.

It's been weeks since then, and I’m still working out how the framing should look—if it’s going to be the main theme, it needs to speak to the history of this place.

Site Plan—Sketch & design by William E. Evans, © 2022

Ground Level Plan—Sketch & design by William E. Evans, © 2022

First Floor Plan—Sketch & design by William E. Evans, © 2022

Second Floor Plan—Sketch & design by William E. Evans, © 2022