Age of the Automobile

Photo by Ivana Cajina on Unsplash

This past Sunday’s newspapers brought an interesting juxtaposition of articles on urban design in the age of the automobile, offering a subject dear to my heart.

The first article was an opinion piece in the Washington Post, Is This the Tysons We Envisioned? by Emily Hamilton.

Silly question, really, but I needed to read it, dope in the vein.

Ms. Hamilton is Director of the GMU Urbanity Project at a university without a school of architecture, let alone urban planning–kinda like a project, maybe? So here we go:

“Ten years ago last month, ahead of four new Silver Line Metrorail stations opening, Fairfax County adopted a 40-year redevelopment plan for Tysons. The goal was to facilitate a new downtown where people could enjoy walking, exercising, supporting local eateries and shops, and easy access to greater D.C. via the new stations. The Plan was heralded by the American Planning Association for seeking to transform a sprawling, highway-oriented areas into a series of transit-oriented walkable neighborhoods. So far, for all its progress, it has not ushered in an era of easy walkability.”

from Is This the Tysons We Envisioned?

Ms. Hamilton’s argument is that Tysons’ environment (and traffic) after the Silver Line is much the same as before, perhaps worse. What a shock! I’ll need my smelling vapors.

Let’s see, first we’ll run a monstrous concrete transit line fifty feet in the air running straight down the middle of Route 7, elevated because putting it underground would cost more.

Pause for vapors!

Then the mavens of traffic engineering will split an already ignomious strip of highway into two separate halves, add turn lanes, lots of traffic lights both sides of each intersection, widen the side roads, put in service lanes, and, oh yeah, don’t forget to add four-foot sidewalks for them three or so poor pedestrians trying to cross two hundred feet of no man’s land. That’ll just about do it for an urban community—or do it in.

Above all else, ensure the stations are as ugly as you can make them!

All those classic vaults and gullwing forms Harry Weese designed? None of those for Tysons. We urbanites in Fairfax love us some out-of-scale ugly. After all, who else shops at Tysons?

And please elevate all the pedestrian access points so the office folk never set feet on the ground moving from office building to station.

What could be wrong with that?

At least Ms. Hamilton can see it didn’t work out, but anyone who can read plans could have told her that before they’d broken ground–at least any architect could.

A number did, including Bill Gallagher–who sat his skinny ass one seat in front of me at Harry Weese. He’s spent a career in transit design, and had a few choice–published–words about the short-sighted decision not to put that stretch of Metro underground.

The former governor of Virginia, Tim Kaine by name, decided it was too steep a leak of Virginia gold to run the line underground–like in, let me see, oh, most of D.C. And that, as they say, was the death knell.

I like Tim Kaine, but he screwed the pooch on that one.

Back then, the proud-as-a-peacock head of Fairfax County’s Office of Economic Development said, “Tysons will become the urban center of Washington!”

Smoking some fine Mendocino ganja, he was.

Contrariwise, the backwoods comedian, Jerry Clower joked about being stuck up a pine tree with a bobcat yelling “Shoot up here amongst us, Cletus! One of us must surely have relief.”

Urban Design 101: First deal with the cars. It can be done. It has been done. Don’t even need to banish them all, just the first couple million or so will do.

So the Silver Line didn’t come with a silver lining. What if Route 7 and Route 123 were buried through Tysons, aka Fairfax County’s downtown?

And if you have no other way but to elevate a transit line, as in, say, Miami-Dade, where the water table’s too high, dedicate a linear park with bike trails and landscaping below so as not to contribute to more pavement.

And for heaven’s sake make the stations “look like an architect has been there” (Harry Weese’s design mantra).

Emily Hamilton – An Economist’s View

I was curious about a writer who the Washington Post considered sufficiently qualified to warrant two column page of text discussing urban planning or the lack thereof in Tysons.

So I googled the GMU Mercatus Center, “Bridging the Gap Between Academic Ideas and Real-World Problems,” as their website proclaims. Scanning the GMU website, economic studies are all to be found. Economics, one of the weakest social sciences in predicting the future.

Even more, it’s curious to find an economist opining on the state of the urban environment.

”Hamilton is a PhD candidate in economics at George Mason University. She is an alumna of the Mercatus Center’s MA Fellowship at George Mason University. She received her BA in economics from Goucher College.” from the Mercatus website.

So that explains that.

Not that economists don’t have right to an opinion regarding urban life, but it takes more than economics to understand how we’ve gotten into the hole we’ve dug so thoroughly.

Namely, that the automobile has distorted life in both urban and rural America the such an extent that we hardly recognize the problems, beginning with the huge environmental cost of pollution–40% of the total carbon output and 75% of carbon monoxide.

The aesthetics (kindly put) of the age of automobiles has left a wasteland of parking lots and roads in its wake.

The history of cotton in the South was one of repetitiously growing the plant until the soil was leached of nutrients, then moving further west to start over again–they got from the Carolinas to Texas before too long.

Likewise, the history of automobiles and shopping malls–first came the close-in strip malls that ruined downtowns from Maine to Florida, then larger and larger malls until you get to the mega malls like Tysons.

Paul Theroux, in Deep South, describes miles of abandoned motels and gas stations along U.S. 301 through South Carolina–after I-95 killed off the traffic.

Similarly, if you drive U.S. 1 south of Alexandria, you can view similar acres of decaying strip malls. Viewed strictly by economics, they are the result of competition; it’s an entirely different story viewed by their environmental damage.

What genius planner in Fairfax County first declaimed Route 7’s strip malls and shopping centers could be made into an urban downtown?

Tysons Corner is the antithesis of urbanity. A monoculture lacking in any kind of diversity, with its back turned to the outside world, backed up to and surrounded by acres of surface and structured parking.

What makes an urban environment vital, its active, diverse community of pedestrians, is leached (or in Tysons’s case, drained and bleached) of its vitality in the age of the automobile.

The Tysons Plan

Hamilton states a Fairfax County taskforce was established to ‘re-envision’ the Tysons area in conjunction with planning for the Metro stations.

“The task force included different types of stakeholders, including representatives of the real estate industry, environmentalists and homeowners from the surrounding neighborhoods.”

from Is This the Tysons We Envisioned?

No architects leading the char? No urban designers? Traffic engineers to be sure–Fairfax County’s idea of a good urban plan is to make the highways go faster–for cars. But folks skilled to envision a place before it’s built, anticipating the outcome? Pray, why would you need them?

The primary reason the original Washington Metro architecture was successful was that ARCHITECTS led the physical design. We were generalists who had been trained in the history of cities and understood them in holistic ways that planners and engineers—focused on the details—aren’t trained to consider.

Architects designed the Washington Metro stations and sites as a piece. We placed pedestrians at the apex of the importance pyramid, followed in descending order by buses, drop-offs then finally private vehicles.

Sad to say, the Silver Line was designed by committee led by a consortium of contractors. To a man with a hammer, everything’s a nail, but what if a nail isn’t what’s needed? Nothing against contractors–they weren’t put on the earth to ‘envision; they were put here to build.

Ms. Hamilton does get one thing right–she sees the traffic hasn’t improved:

“It [the Tysons Plan] has failed to make the area as walkable and transit-friendly as it’s supposed to be. It also failed to reduce the number of car trips in and out of the area, relative to the 2011 baseline.”

from Is This the Tysons We Envisioned?

But we love our cars in Fairfax. Might as well be living in Dallas-Fort Worth. The newer, western end of the county has eight lane suburban arterial streets that remind ever so much of a Texas suburb, sprawling as far as the eye can see. Mainly because the traffic engineers said we needed road capacity above all else.

An Olympic sprinter like Usain Bolt might make it all the way across one of those intersections, but old Aunt Ethel never could.

No lipstick will help this pig.

Absent demolishing the newly completed Silver Line through Tysons and burying it as it should have been in the first place, at this point, I’d suggest backfilling everything around the stations, burying Route 7 and starting over—thirty feet or higher. It could look like Underground Atlanta for the Walmart generation.

Give future archeologists something to dig for.

In nearly the same timeframe as Bostonians tore down their elevated section of I-95 that had gutted the heart of their city, spending billions to bury it, Fairfax County just got themselves a brand new ugly-assed pig to go with their even uglier poke of strip malls affectionately called Tysons.

Ms. Hamilton concludes her WP article by entirely missing the point, a swing and a miss as they say:

“The Tysons approach provides one proven way to successfully bring about suburban densification [sic]. By appointing a task force to determine how, not whether, Tysons would be redeveloped, and by appointing members with diverse interests, Fairfax policymakers set the effort to succeed… The major roads cutting through Tysons remain hazardous to pedestrians and present a potentially insurmountable obstacle to widespread walkability. Fairfax policymakers have not yet shown how to manage the politics of this final step that is necessary to their vision.” Emphasis added.

from Is This the Tysons We Envisioned?

She’s right about the policymakers not managing the politics–or the problem. What escaped her (along with the Washington Post editors) is that the policymakers have now made the problem close to intractable. Who’s going to tear down several billion dollars of bad design?

Fun With Numbers

It is estimated that for every non-commercial vehicle, there are seven to eight separate parking spaces made available for it on average across the United States. Between the zoning laws and merchants who want your business, that’s a rough estimate of just the parking. Given Americans’ propensity to avoid walking–if they can’t park withing ten feet of the front door, they’ll drive to where they can–collectively we’ve cheerfully paved an enormous swath of the country in asphalt.

In cities it’s worst. Houston has something like 30 parking spaces per car. And overall, cities easily give up 50% of their entire urban area to vehicles for roads and parking lots. Even in a city like New York.

Tysons is more like 70% covered in asphalt–that’s not my kind of urban landscape. Nor is it likely to change.

So, please allow a short digression for the numbers. Or skip to the last line in bold if you like; I won’t tell.

Each parking space takes up 270 square feet [1] for cars and 360 square feet for commercial trucks.

In 2020, the total number of vehicles is estimated at 287.3 million [2] of which approximately 60% - 70% are personal cars and light trucks (i.e. SUVs, et al.).

Parking must be provided for approximately 172.4 million to 201.1 million non-commercial vehicles. Commercial vehicles take up space as well, but the data on them isn’t easy to find, so just assume 3 spaces per commercial vehicles.

172.4 million non-commercial vehicles x 270 sq. ft. x 7 to 8 spaces per vehicle = 325.8 billion to 372.3 billion square feet.

114.9 million commercial vehicles x 360 sq. ft. x 3 spaces = 124.1 billion

Totaling these crude calcs = 450 billion to 496.5 billion sq. ft. of surface parking.

We have paved 16,140 to 17,809 square miles–greater than the state of Delaware, or roughly the size of Maryland JUST FOR PARKING in this country.

[1] 9 ft x 18 ft space, plus 9 ft x 12 ft drive aisle = 270 square feet for each parking space, not including roads.

[2] From Hedges Automotive Market Research

Sitting side by side with Ms. Hamilton’s article in Sunday’s Washington Post was another one about transportation titled A covid-19 silver lining: Better roads written by the head of the Maryland Department of Transportation State Highway Administration. The article talks about how much easier it’s been, with the shutdown, for highway construction to proceed. We spend more money on roads and single occupant vehicles than all manner of public transportation because the citizenry demands it. Even in Maryland.

I rest my case.

Manhattan Dreaming

I’ve Seen A Future Without Cars, And It’s Amazing was last Sunday’s New York Times article written by Farhad Manjoo. And very cool graphics accompany the article’s online version. Graphics courtesy of an architectural firm. Graphics are how architects communicate, and hats off to these architects.

“Architect: A master-builder. A skilled professor of the art of building, whose business it is to prepare the plans of edifices, and exercise a general superintendence over the course of their erection.” OED

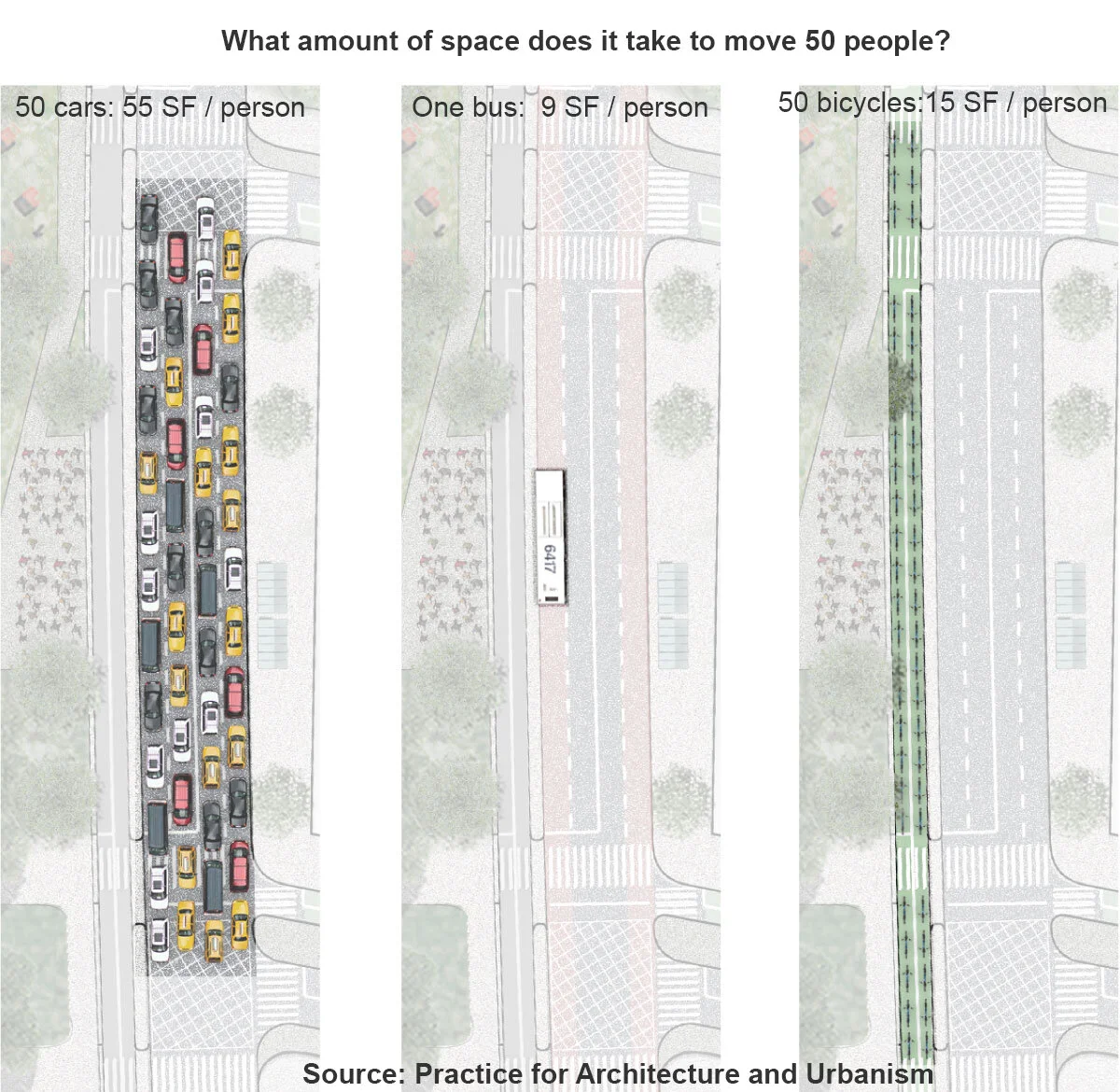

Farhad Manjoo proposes banning private vehicles from the island of Manhattan–all of them. And I don’t even think he’s being paid by the taxicab lobby. He quotes an architect, shockingly, on what the city could do with the reclaimed area now occupied by traffic. First, he talks about the reduction in pollution, traffic accidents and fatalities during the City’s recent Covid shutdown. Then introduces Practice for Architecture and Urbanism, PAU.

“In the most car-dependent cities, the amount of space devoted to automobiles reaches truly ridiculous levels. In Los Angeles, for instance, land for parking exceeds the entire land area of Manhattan, enough space to house almost a million more people at Los Angeles’s prevailing density.

“This isn’t a big deal in the parts of America where space is seemingly endless. But in the most populated cities, physical space is just about the most precious resource there is. The land value of Manhattan alone is estimated to top $1.7 trillion. Why are we giving so much of it to cars?”

From I’ve Seen A Future Without Cars And It’s Amazing by Farhad Manjoo

Banning private vehicles would be, I suspect, more difficult than Mayor Bloomberg’s unsuccessful soft drink ban in the Big Apple. I think it’s written somewhere in the U.S. Constitution that driving an SUV is a basic American right.

And how could it be enforced, say, in New York City? How would one know if the limo taxi wasn’t a Russian oligarch being chauffeured in his Lincoln? I kid the Russian oligarchs–who else would pay such outrageous prices for a Manhattan apartment?

The graphic conveys, in three side-by-side images, the automobile’s real impact on land use. Perhaps the removal of all private vehicles is a pipe dream, but there are certainly less drastic steps cities could take to improve urban settings. Would replacing parking for bike lanes be considered? Perhaps a phased introduction by way of selective streets? One side parking only? Only alternate blocks with parking?

By way of example, the last block of King Street in Old Town Alexandria has taken a less drastic turn–brought on by the Covid–banning street parking and allowing restaurants to expand outdoor seating (complying with social distancing). On pre-Covid weekends, pedestrians spilled out onto the road while maneuvering King Street’s narrow sidewalks as the cars idled in place. Perhaps post-Covid the city officials will consider closing the street all together on the weekends? Just the block closest to the river, perhaps?

Pretty please?

If King Street were closed to all but Alexandria’s free trolley service, it would, with a single stroke, create the same pedestrian freedom that a streetcar system engenders without the cost.

Tysons Redux

With the horse (if not the horsepower) long out of the barn, about the only options for improving the urban environment for “Fairfax County’s Downtown” is to re-route the vehicular traffic around the hoped-for core, bury Route 7, or remove it altogether. Napoleon III hired Baron Haussmann to level whole sections of historic Paris to create his city of grand avenues.

Surely no one’s going to miss Route 7, are they? Even the name doesn’t have decent curb appeal as the real estate ladies like to say.